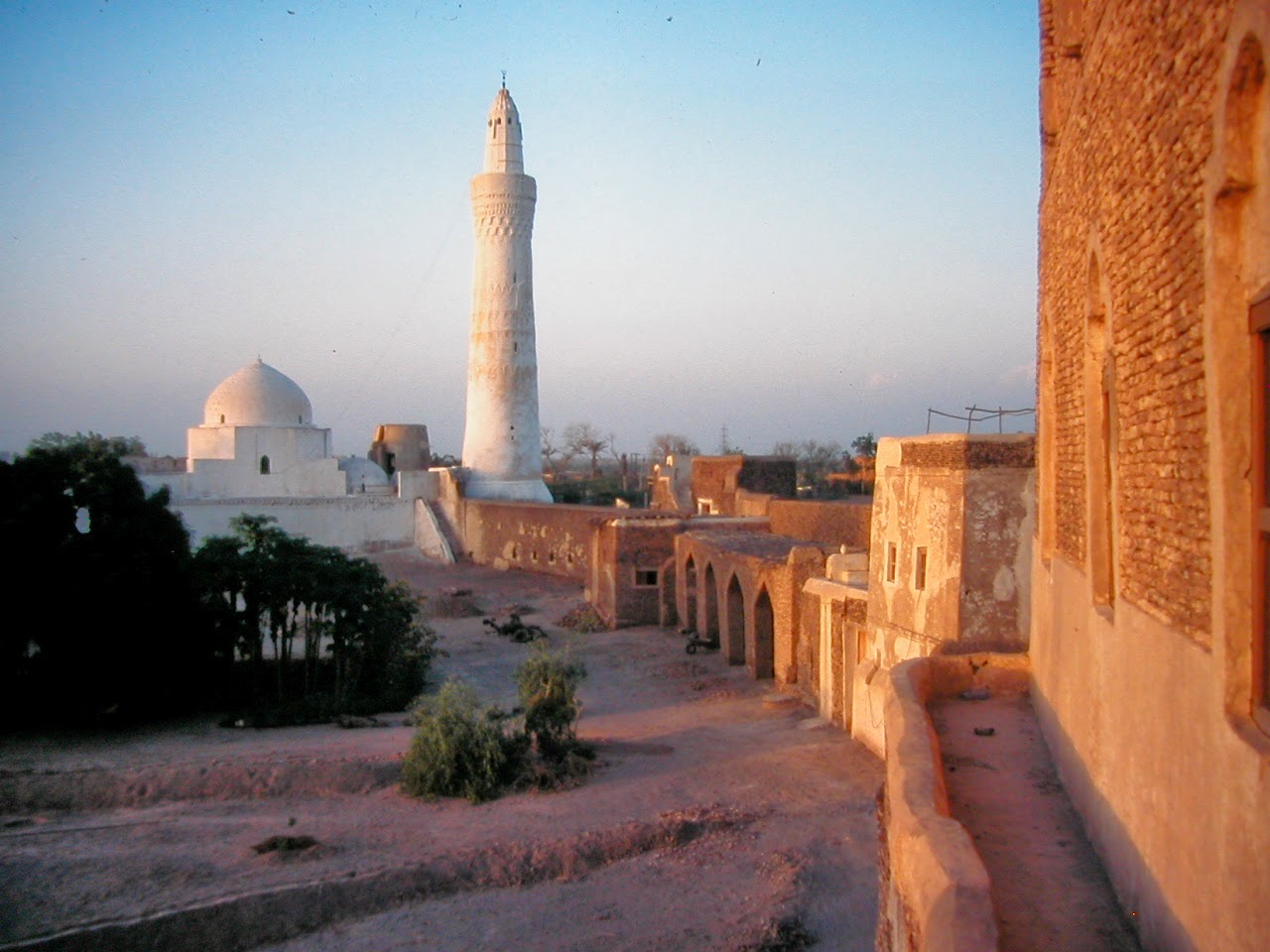

Last tango in Zabid, 1999.

|

| Iskandar Mawz Mosque, Zabid |

In a translated account of Ibn Battuta, an Islamic traveller who had visited Zabid during his peregrinations in the fourteenth century, he reported:

Zabid is a distance of forty farsakhs [one hundred and twenty miles] from San’a and after San’a the largest and wealthiest town in al-Yaman. It lies amidst luxuriant gardens with many streams and fruits, such as bananas and the like… The town is large and populous with palm-groves, orchard--in fact, the pleasantest and most beautiful town in al-Yaman. (TMS 2000:84)

|

| Looking south from the Citadel. |

We stopped opposite the old Citadel at a familiar site—the small shaded teahouse on the main square that I had frequented on my previous sojourn. Back then, it was the trees and shade that attracted me and our dig crew to this place, especially on hot afternoons and our days off when you would find us relaxing in the shade with fresh cool fruit juices, and chatting with curious local urchins. Often we came to get a lime mixer that we would later add to our sundowners back in the privacy of the Citadel.

I was just about to give up when I heard voices coming from the old kitchen. I peered through the wire fence, I saw coming from out of the kitchen, a familiar face from the past. It was Muhammad, the son of Ahmed, our dig’s general handyman. Hoping he remembered me, I shouted out his name.

‘Muhammad!’

He looked at me oddly at first as if he was trying to figure out who I was and, more importantly, how I knew his name. It was time for a bit of my Arabic. In the best accent I could muster, I asked him:

‘Muhammad, wayn baba?’ (‘Muhammad, where’s your father?’)

He still looked dumbfounded.

‘Ana, Emerson,’ I said. (‘I’m Emerson.’)

Suddenly from behind, I heard a voice yelling at me. I turned around to find Jabbar, the Citadel’s guide, and Muhammad’s father, Ahmed (the handyman). Dressed of course in the traditional Tihama futa, Ahmed looked thinner than I remembered, but he was still wearing his oversized Sammy Davis sunglasses. He must have recognized me because on his face was a wide grin revealing a few more missing teeth and his cleft palate.

‘Kef halak habibi?’ (How are you my dear?) He asked.

‘Tamam,’ I said. ‘Al hamdulillah.’ (Fine, thanks be to God.)

Showing off the little bit of English he knew, he asked: ‘How is you?’

‘I’m fine. Kwayiss!’

I stuck out my hand to shake his but instead he grabbed and kissed my wrist as a sign of respect. Then in usual Yemeni fashion we hugged. From a large clutch of keys, he took one and unlocked the gate. Once inside, I gave Muhammad a hug and couldn’t help but notice that since I last saw him in 1996 he had grown up to be as tall as his father.

We went to sit down at one my favourite spots to relax—a low plaster bench now thankfully in the shade outside the mudbrick kitchen. It was a godsend to meet these chaps and catch up on old times.

‘Wayn mudhir?’ (‘Where’s the mudhir?’) I asked.

‘Sana’a,’ said Ahmed, then he mentioned a common acquaintance, Johnny Al Bayti, a student whom I had met in the Islamic Archaeology course at the University of Toronto a few years back. Johnny was a Syrian-Canadian who had worked on the dig for years but had skipped the year that I was there because of security issues on the proposed coastal dig where he was to do underwater archaeology. As his Arabic was fluent he had now become the mudhir’s second-in-command.

‘Wayn Johnny, Muhammad and Abdul Habib?’

‘They are here but on the coast,’ said Jabbar in excellent English.

‘When are they coming back?’

‘Inshallah,’ Jabbar said. ‘They should be here soon.’ In this culture “soon” could be tomorrow, next week or next month.

Then Ahmed interjected that they were expected back that very day.

‘When will the mudhir get here?’ I asked.

‘Maybe this week or next,’ said Jabbar. He probably had no idea when the mudhir would show up but was just being polite.

It would have been nice to see the old gang again but unfortunately, I did not have time to hang around. Our ‘programme’ had us continuing onto Ta’izz where we would stay tonight. I briefly considered spending the night here back at my old perch on top of the kitchen roof, but here in the Tihama where life usually moves slowly we were doing a whirlwind tour and time was ticking away. If we didn’t get going after this unscheduled stop, Khaled would be kicking his heels outside the Citadel chomping at the bit to get going. I decided to let him chomp. It was that old pecking order thing again.

|

| Fatini, the cook with Carl |

Perhaps the reason the place looked so unkempt was because it had been dormant since the last dig season almost nine months ago. Walking through the dusty dining area, I could scarcely believe that this was the place where we’d had so many raucous and delicious mid-day meals that our pirate cook Fatini had lovingly prepared for us. Because there was no fresh air circulating now, there was a definite pong to the place. I poked my head into the kitchen where I used to cook breakfast for myself and the occasional dinner for some of the Yemeni staff. Egads, but I would not want to be cooking here now. Sadly, it now seemed quite grotesque and extremely unsanitary. Unfit for habitation actually.

Since my last trip, fluorescent lights had been installed inside and outside but their presence detracted from the mediaeval atmosphere of the place. This alteration in the ambience was due to more than the mere presence of the fluorescent lights—the whole place looked dilapidated: palm fronds were missing from the roof of the mudhir’s pottery yard, discarded sherds littered the terrace, and where Carl used to do his meticulous conservation of artefacts there was a thick layer of dirt.

|

| Carl with the garden |

‘Ahmed,’ I asked, as I motioned to the spot where the papayas once stood. ‘Wayn papaya?’

‘Finich,’ said Ahmed. ‘Mafi papaya! Finich!’

‘Leish, mafi papaya?’

‘Mafi faloose,’ he said. ‘Karaba kitheer.’ What he meant was that it cost the mudhir too much money to irrigate the papaya trees and banana palms which together would consume a considerable amount of water during the nine months when he was back in Canada. At first, Ahmed had earned some pocket money from the papayas, that is, if I did not eat them first, but now, as he settled down for his afternoon sheesha, he just seemed to accept his fate calmly, the characteristic of fatalism so common amongst the believers. Some things never change, Inshallah!

In the garden, I went for a stroll down memory lane. Many an afternoon—to get away from the blinding glare of the sun shining on the whitewashed buildings, and the oppressive heat of my trench outside the Citadel—I relaxed on a Tihama bed here in the cool shade. Then the garden had been lush with papaya trees, banana palms, and nasturtiums, now, other than some towering eucalyptus trees and a few scrawny bushes, nothing was growing out of the bare earth. It had not taken the good old days long to disappear.

|

| My old sleeping quarters. |

Working in the Citadel in 1996 had meant so much to me at the time but I also remembered that it was a turning point in my life. My mother had died after a prolonged bout of pancreatic cancer only two months before I joined the dig because it seemed like a good idea to get away the all the grief I had felt back home in Toronto. At the time, I also knew that I probably would not pursue a career in archaeology. I’d had my fill of academia; the dig had its ups but mostly downs because of the irrational edicts of the mudhir. Without a doubt, this mudhir was the worst guy I’d ever worked under on a dig. Obviously, depending on your position in the pecking order it has its faults. As it happened, within a year, I would be back in the Middle East, but as a teacher of English as a Second Language and finally be making good money to be able to afford a trip like this one to Yemen. As an archaeologist I was always as poor as a mouse in a mosque!

Looking out over my old bailiwick, I felt I was cheating my memory by leaving after only a few hours. As much as I wanted to stay there, I still wanted to get the hell out of there. I bid the staff farewell, and headed back for the last time, perhaps, through the whitewashed Bab el-Kebir and there was Khaled waiting for me at the tea-house. I was licking my lips thinking about of the fruity cocktail mixes that we used to drink here on sultry afternoons chit chatting the time away, so I asked the tea-shop owner, ‘Mumkin mix? Cocktail?’ (Maybe mix, cocktail?)

‘Mafi cocktail,’ said the owner. ‘Khalas!’ (No cocktail! Finished!)

Apparently, since my last time here things had changed.

Just as we were leaving the place, Ahmed dashed over to say that Johnny, Muhammad and Habib had indeed just arrived at the citadel. Khaled rolled his eyes at another last minute delay. I hurried back to the Citadel for a quick reunion with my ‘Yemeni boys’.

Muhammad still had the huge Cheshire cat smile and Habib was his usual quiet self. Their shabby appearance had not changed a bit but their English had improved dramatically.

‘How are you?’ I asked

‘We are fine and you?’

‘Kwayiss.’ I said.

They both laughed at my Arabic.

Johnny was still the same lanky dig rat that I knew from our days at University of Toronto. We chatted a bit and then headed off to the newest watering hole in town—the Zabid Guest House whose advertisement I had seen on entering the town.

The Zabid Guest House was the place in town to cool off and relax in the shade of an expansive barasti roof. This guesthouse was a welcome addition to Zabid’s meagre social scene. It was not around when I was last here. It even had two pool tables that Johnny told me the ‘boys’ would shoot pool after a day’s dirty work on the dig. I was a bit surprised to see women with uncovered hair working here.

‘Who are these women?’

‘They are local women.’

‘What are they doing here in the guesthouse?’

Winking and giving me a nudge, Johnny said slyly, ‘You know.’

It did indeed look like one might be able to flirt with some of the Tihama gals that were working here, or at least that was what Johnny intimated to me but in this conservative society, I found it hard to believe!

Over cold soft drinks, Johnny and I talked at length about the state of archaeology, Muhammad and Habib were able to join in as they had been studying English at the American Institute in Sana’a. We discussed the pros and cons of archaeology as a career and Johnny asked me why I had left archaeology.

‘Because I couldn’t get steady work,’ I said. ‘I was tired of waiting for contract work on the West Coast in British Columbia. Instead I did a TESL certification course and soon found full employment in Korea then six months later did a runner to UAE.

‘Besides I’m a Near Eastern archaeologist,’ I said, ‘and if I worked on the West Coast, I would be at the bottom of the pecking order, I’d have to start all over again learning a new material culture of Canada’s First Nations.’

I told him how once my friend Serge and I had worked on another friend’s dig in northern Ontario near Temagami where after a mere foot of digging, I had hit the bedrock of the Canadian Shield. There were no historical levels here to interpret, unlike a site northern Syria in 1992, where we excavated a multitude of occupation periods and destructions levels to a depth of more than five meters and we eventually dug down to 10,000 year-old Neolithic layers. Johnny sympathized with my plight.

Johnny told me all about how he was trying to persuade IMF officials to part with their money for various reconstruction programs in the Citadel and the adjoining Iskandar Mosque. I wished him luck on that as that seemed an insurmountable task.

We had just gone outside the guesthouse to say our final goodbyes when unexpectedly we ran into our old night watchman, Misgagi. He hadn’t changed a bit since I last saw him in 1996. Johnny then told me that Misgagi had lost his baby girl during Ramadan, which must have been difficult for him and his wife. In watching the ease with which Johnny could converse with these locals, I realized that, as a site supervisor, he had one huge advantage over me: he could speak fluent Arabic and I couldn’t.

On reflection, maybe Johnny and I were living in a make believe world of archaeology. I always hoped that I could make a living at it but, in reality, without a PhD, most digs lasted only four months, and thus one was forced to constantly live from dig to dig. Despite that, I always loved the time I spent on archaeology in the Middle East and missed that bohemian lifestyle. To me archaeology never seemed like a job, but a passion. It was never difficult to roust yourself each morning to work on a dig. At a lecture I was giving on archaeology, someone once asked me what was the most interesting object I had ever found on a dig; my answer: ‘The next thing I uncover.’

Finally, we bade each other farewell, promising to keep in touch, which, unfortunately, we never did. [ii]

When I got into our baking vehicle, Khaled floored it out of there.