The Spice Island

Not having sea legs,

sailing is the least acceptable way of travel for me, especially when you are getting

coated in salty spray accompanied by the searing African sun beating down on you. Our travelling quintet consisted of my two Aussie mates Phil and Michael, the California surfer gal Loy, Lars the

Swede and me. We were sailing to Zanzibar. None of us had been here before so this was terra incognita.

Most of us had sought the shade of the sails but there was no comfortable place to sit except for some rough-hewn wooden planks. The trip was monotonous and the only diversion was a school of flying fish and a pod of porpoises that accompanied us for a brief part of the voyage. Nevertheless, between the antibiotics and the fresh salty sea breeze, my sinuses and chest had cleared and I felt my old self again—ready for another adventure.

Most of us had sought the shade of the sails but there was no comfortable place to sit except for some rough-hewn wooden planks. The trip was monotonous and the only diversion was a school of flying fish and a pod of porpoises that accompanied us for a brief part of the voyage. Nevertheless, between the antibiotics and the fresh salty sea breeze, my sinuses and chest had cleared and I felt my old self again—ready for another adventure.

What a relief! We were

finally on the island of Zanzibar.

|

| Zanzibari kids |

|

| Doctor Livingstone at Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe |

The island enjoyed this

brief independence from the mainland but then pressure from Britain and

Tanganyika’s mainland political party, TANU, weakened the new republic.

Eventually, Zanzibar succumbed to Julius Nyerere’s socialist party TANU and

formed Tanzania in 1964. The word TANZANIA is a portmanteau of the former British

Protectorate of Tanganyika and the islands of Zanzibar.

Despite being part of the

‘new’ Tanzania, Zanzibar still remains a semi-autonomous region beholden to no

one, especially to mainlanders and their African-dominated politics. Truth be

told, Zanzibar’s roots are in the Islamic sultanate of Oman. Zanzibari

families, the ivory and slave trade are historically tied to Oman rather than

to the Christian and animist African cultures of mainland Tanganyika.

It was into this rich

history that we first stepped off the ferry and onto the fabled island. Accommodation

in historical Stone Town was minimal. We thought we had lucked out when we

found Malindi Guest House, but all the rooms were taken? I think the hotel

manager took pity on us as it was getting dark so he said that we could sleep

on the marble floor in the lobby for a small fee.

We dropped off our gear then

enjoyed a local favourite, mishkaki or sticks of BBQ meat, as we walked

around Stone Town where we ran into a local guy named Zakwan. We mentioned to

him our fear about getting stuck on the island. In conversations over a warm

beer, he told us that he had friends at customs and the port authority who

might be able to arrange our later transport back to Bagamoyo.

* * *

|

| Stone Town kids |

The islands of Zanzibar and

Pemba are also known as the Spice Islands because of the abundance of cloves,

pepper, cardamom and nutmeg plantations. At one time, Zanzibar controlled 90%

of the clove trade in the world. As we were walking around Stone Town,

depending on which way the wind blew, there was the unforgettable scent of

cloves. It was much like being around a freshly baked pumpkin pie.

* * *

Between mosque and rooster

calls, I was up early, so I ventured into Stone Town for something to eat. Overcome

by humidity, I sought the shade of a huge baobab tree near the town’s center. While

enjoying a pre-breakfast snack of spicy potato samosas, I noticed a

Japanese tourist haggling over something with a local in fluent Swahili no less.

The food seller next to me caught my perplexed glance—it begged a question.

‘I don’t see many Japanese

tourists here?’ I asked.

He just nodded.

I had been aware that

spoken Japanese and Swahili had some similarities in their languages,

especially the word endings—kawa, dawa, sawa, and from

overhearing the haggling, I assumed that this man had picked up the local

lingo.

‘I’m surprised,’ I said.

‘Where did this Japanese guy learn Swahili so well?’

The local Zanzibari

laughed, ‘He’s not Japanese,’ he said. ‘He’s from here!’

My interest was piqued. As

far as I was concerned, he was either Japanese or Chinese and I could not

fathom how he had learned Swahili so well. Later, I found out that there was an

island along the northern Swahili Coast that had an unusual population of Asian-looking

locals. This was the island of Siyu, which is part of the Lamu Archipelago in Kenya that borders the most southern most part of Somalia.

According to the legend, in

1405, the famous Chinese seafarer, Admiral Zheng’s, ship had crashed on the Kenyan coastal reef

and the sailors came ashore where they found villagers who were being

terrorized by a giant python. They killed the beast, and subsequently, the villagers accepted the Chinese sailors, with even some intermarrying, thus creating a new

mixed race. Hence the Asian features of this Swahili guy. Well, it’s a

marvelous story and judging from the ease that this Asian-looking Swahili guy

conversed with the local Arab guy—who could argue? Perhaps this guy’s family

had migrated down to Zanzibar on one of the frequent jifrazis

(ocean-going dhows) that ply their trade up and down the Swahili Coast.

Abandoned beach house on Chwaka Beach

Loy had arranged renting a

beach house on the other side of the island for our growing group of eleven:

the original quartet, Lars, two Brit gals, two American guys, and a Dutch

couple.

After buying some

groceries, we schlepped our backpacks quite a distance to get to the bus

station. Somewhere along our route, our two groups got separated. I thought the

Brit girls knew the way but we took a wrong turn and lost the others. We

arrived to an empty bus station. Unbeknownst to us, the others had lucked out

and already got a lift to Chwaka Beach.

We eventually caught a ride

on a dala dala or a wooden frame bus which took us on a milk run to

Chwaka Beach. En route, we drove past lush coconut and banana groves, and spice

plantations—all verdant and musty. An hour later, in the dark, we finally

arrived at the beach house but we were still pissed off at Phil and the gang

for not waiting for us.

Loy and the other girls had

prepared a tasty curry and vegetarian dish for dinner. To prevent legions of

cockroaches invading our dirty dishes, Phil, Michael, Lars and I washed our

dishes in well water that was brackish and not potable. After that, we played

card games late into the night accompanied by some spirituous libations on the

verandah.

The rooms inside were too

stuffy to sleep in so we dragged the mattresses off the beds out to the

verandah. I hung my mosquito net out there hoping that I could catch whatever

evening breeze was present. Since leaving South Africa, I used my mosquito net every

night. Everyone but me thought that being on the malaria prophylaxis was enough

but that soon turned out to be false. In all of Africa, Zanzibar was probably

one of the worst places for getting malaria, as the coastal mosquitoes had,

over time, become chloroquine-resistant. Nevertheless, we all doused ourselves

in bug juice but I was the only one who slept under a net.

* * *

|

| Michael Collins at beach house, 1984. |

It was not a big deal at

first, but it did not heal, and a few days later this innocuous cut had become

septic. Luckily, Loy had some disinfectant soap and antibiotic cream to treat my

wound. However, I was still worried about getting a tropical ulcer so to

protect my foot while wearing sandals, I cut the toes off the end of a sock.

Later in the market, while I was wearing the sock and a sombrero tilted at a

rakish angle, I looked so odd, like a demented dandy on holiday. Phil just had

to take a photo of me.

|

| L-R. Michael Collins, Bionic Lars, and me with my gammy foot, Stone Town, 1984. |

Our Chwaka Beach House had

bugger all for amenities: no running water, no indoor plumbing, never had

electricity, it was just a shell of a former grandiose beach house. It had a huge kitchen with blackened spots,

plenty of airy rooms and, best of all, a wide verandah at the front. We used

stinky hurricane lamps for light.

|

| Handyman scaling the coconut palm. |

The main attraction of our

beach house was the wide verandah at the front of the house which gave us an

unhindered view of the Arabian Sea that was just a few feet from the beach

house. The verandah also afforded us a superb view for watching spectacular

sunrises with our breakfast and marveling at fiery sunsets with our sundowners.

Of our newfound Brit companions,

Val was a bra less, buxom blonde with a punk haircut which pre-dated Sinead

O’Connor’s buzz cut—this was 1984 after all. She was a bit cheeky and could be

a smart-ass. On the other hand, her long dark-haired friend Jenny was timid by

comparison but attractive nonetheless. At times, they came across as a gay

couple but maybe were just close friends. This was no big deal for our group

but this was the 1980s and we were in an Islamic culture after all. If they

were openly gay this might have created serious complications on conservative Zanzibar.

Perhaps that is why they were travelling with us.

Compared to Loy, these two

Brit gals came across as louts. Perhaps Loy’s intelligence and no nonsense

American panache made them uncomfortable in her presence. At any rate, Loy had

been a real trooper from the get go, slugging it out from Malawi with Phil,

Michael and me. For that matter, because she had a great heart and a wonderful

sense of humour, she was an ideal travelling companion.

After a few days in

paradise, Phil, Michael, Lars and I decided we’d had enough of this bohemian

beach life and we would be leaving the following morning. The three girls

decided they would stay for an extra day—they were welcome to it.

The hurricane lamps on the

verandah were flickering low, the mosquitoes were buzzing around, our liquour

was drunk as were we—I passed out in my mosquito net as a soft tide washed in

from the Indian Ocean and lapped close to our beach house.

* * *

The next morning, our last

morning at the beach house, Neil came up from downstairs where he had been

sleeping. We were all slightly hung-over from the merry-making last night and were

still shaking off the cobwebs of alcohol. He looked slightly perturbed.

‘Have you guys seen my

flashlight?’ Neil asked.

‘Did you guys use it up here?’

‘No,’ I said, ‘Where did

you leave it?’

‘I thought it was by my

bed,’ he said, ‘I’m also missing my shoes, my jeans, a t-shirt...’

Phil, Michael and I looked

at each other, wondering what he was on about. Then we frantically checked our

own packs that were scattered carelessly on the verandah.

‘Hang about,’ said Phil,

checking through his pack, ‘someone’s nicked my cigarette lighters and a

t-shirt.’

Then I remembered that I

had leant my Swiss Army knife to Lars to scale and gut the fish for last

night’s dinner.

‘Did you give me back my

knife?’ I asked Lars.

‘Yah sure,’ he said.

‘Damn!’ I said, rummaging through

my pack, ‘Someone’s stolen my Swiss Army knife.’

So, in our drunken sleep state

last night, some light-handed (and light-footed) thief had made off with our

valuables. Not a good way to begin our morning. I guess it was time to leave after

all!

In deciding to leave, our

neat little quartet of travellers, Phil, Michael, Loy and me, had come to its

end, and unfortunately, under bad circumstances. We exchanged hugs and

addresses with Loy. We bid her farewell as she’d been a good sport throughout

our trip that began back on Lake Malawi. We’d been through a lot together in

our short time and I would miss her spirit and great meals that she made us

along our tough borderlands trek.

We made tentative plans to all

meet up back either in Dar or Nairobi but we never did see her again. A year

later, I received a postcard from her and she told me she was stricken with

malaria while staying in Dar.

Back to Stone Town

After farewells, we grabbed

what stuff we still owned, hurried over to the dala-dala station for a

ride back to Stone Town. While Neil went to report our stolen goods at a nearby

police station, we had a cup of chai at a nearby duka. Unlucky

for Neil, our dala-dala arrived while he was still in the station. Remembering

what had happened a few days before, we hopped on and sped towards Stone Town

thinking he could catch a later one.

|

| Zanzibari door, Stone Town. |

Zakwan had previously said

he could find us transport off the island but when we found him he said there

was nothing leaving today. He did find us two captains who were going to Dar

later in the afternoon. We jumped at the chance and all of us went to the

Immigration office to get exit stamps. While there, Zakwan introduced us to two

officers on duty: a younger and older guy.

‘When are you leaving?’

Asked the older officer.

‘Today. On a dhow,’ said

Phil.

‘You are not allowed to

travel by dhow!’ He said. ‘It’s too dangerous.’

‘You are allowed to travel

by motor boat,’ added the younger officer.

‘But you must first get

permission from the Tourist Office,’ said the older officer.

That office was at the

other end of the town—sheesh!

After telling him of our

ordeal in Zambia, just being robbed last night, the older officer seemed to

soften and we got written permission from him. We moseyed around town, then

walked back to Customs & Immigration offices around 2pm. They told us we

had just missed a motorboat going to Bagamoyo which really pissed us off. We

were sweaty and tired from the heat and the walking.

‘Are there any other boats

leaving today?’ Phil asked.

‘No, but come back tomorrow,’

said the older officer with a smile.

Phil, Michael, Lars and I

were shattered by this news. We treated ourselves to some freshly crushed sugar

cane juice which seemed to revive our spirits. Still dying of thirst, I ordered

some fresh tamarind juice which seemed to temper it momentarily.

* * *

| Slave Square, Stone Town, Zanzibar |

It was ironic that the

Anglican Cathedral of Christ Church, finished in 1873, overlooks the former slave

square and monument. Some say the cathedral’s altar was built directly over the

spot where the slave whipping post had been. As it happened, I was the only one

there. No locals came by to pester me, and I wondered if for the locals,

perhaps, the shame was too much to bear.

* * *

Back at the Malindi Guest

House, we paid up for the night, took a shower, met Neil and hung out chatting

about getting off the island. In the evening, when it was somewhat cooler, we

strode down to the beachfront for some grub. My favourite refreshment was

freshly quartered slices of green mango, slathered in red chili paste and

slaked with freshly squeezed lime juice. In this torpid climate that seemed to

do the trick. The deep fried plantain with red-hot chili paste also hit the

spot naturally followed by tamarind juice.

Some guys were loading

boats, and after talking to the captain, they said they would be heading to Dar

tomorrow morning at 9am.

‘How much do you charge?’

Phil asked.

The captain laughed, ‘there’s

a few more people going so you can go for free.’

We could not believe our

luck because by this time, we had given up hope of finding a boat to Dar

anytime soon. Between the humidity, being ripped off, the mosquitoes and

hassles with the boats—we just wanted to get off the island.

Buoyed by our newfound

luck, Phil, Michael, Lars, Neil and I found a pub where we hoped to drown our

earlier sorrows over a few cold beers. We also enjoyed a fine seafood meal at

the Blue Dolphin Restaurant, then went to the Africa House Hotel where there

was a solemn crowd watching someone’s picture on the TV. Sadly, the Prime

Minister of Tanzania, Edward Sokoine, had died in a tragic car accident. The

atmosphere was intense and sullen, so we withdrew back to our guest house.

* * *

Up and early the next

morning, Phil, Michael, Lars and I hot-footed it back to the Immigration Office

to get our passports stamped for leaving, telling them we had found a motor

boat to Dar. As duly instructed by the captain the day before, we arrived at

the boat at the agreed time. They were not leaving yet as they had to wait for

the tide to come in.

‘Come back in an hour and a

half,’ said the captain.

Just then, we met an old

Zanzibari guy named Ali who offered us a guided tour of Stone Town. We had an

hour to kill so what the heck, besides you never know when you might get back

here again if ever?

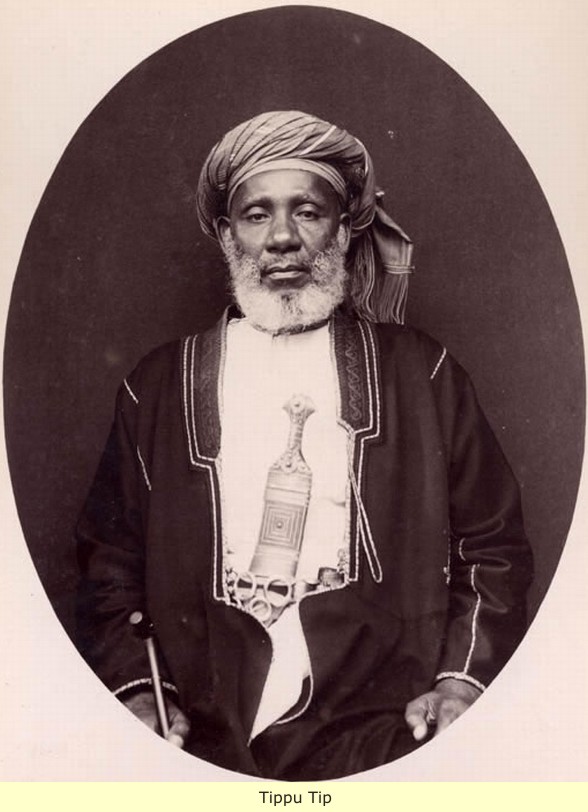

| Tippu Tip's house |

|

| Tippu Tip |

* * *

Zanzibar’s heydays had been

during the Victorian era explorers and adventurers used it as a base for their

expeditions, especially for their porter who were mostly slaves. However, over

the years, both the island and its accommodation had fallen off the charts and

it seemed now unprepared for the onslaught of travellers in the 1980s. The

guide books mentioned only a few places to stay and, we got almost all of our

information from other travellers.

In 1984, Zanzibar was not

exactly “tourist friendly”. It would be about ten more years before it became

one of the ‘big’ tourist attractions on the East African coast usually included

in a safari package. During the 1980s, it was the Kenyan coastal towns of

Mombasa, Malindi and Lamu that were the destinations of choice for holiday

seekers and weary overlanders.

I preferred Lamu to

Zanzibar because Lamu was quaint—no vehicles, narrow streets, donkeys as the

main form of transport, and it was a lot easier to get to. Moreover, Lamu had

kept its Swahili heritage by adhering to strict building codes that maintained

traditional rag coral construction, boriti (mangrove) roof supports, and

palm frond roofing material; Zanzibar had switched to more conventional

building materials, i.e. concrete blocks, corrugated metal roofs and breeze-block construction. I was to find out later that film companies used modern-day Lamu

as Victorian-period Zanzibar, i.e. in the Mountains of the Moon.

We finally arranged a boat that would take us off

the Spice Island, but that’s another story.